Carl Sandburg famously labeled Chicago the Hog Butcher for the World, Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat … City of the Big Shoulders.

In the enthralling, wide-ranging and richly detailed eight-part documentary series “Chicago Stories” on WTTW-Channel 11, we’re reminded Chicago is also the City of Terrible Fires, a Reversible River, the Pullman Car, the Boss and the Bulldozer, and much more. It’s great stuff with a particular appeal to Chicagoans old and new.

Premiering Friday, with a new 60-minute chapter each week, “Chicago Stories” follows a reliable formula throughout. With Chicago-born actor Anthony Fleming III (“Prison Break,” “Power Book IV: Force”) providing smooth and authoritative narration, each documentary relies on time-honored journalistic tools of effective historical storytelling: photos and illustrations and archival footage; straightforward graphics; and interviews with authors, TV and print journalists, historians, museum curators and those who were witnesses (or the descendants of witnesses) to key moments in Chicago’s great, booming, bustling, exhilarating but also troubling history.

Let’s take a walk through the first four episodes, with the promise to review the final four chapters down the road a bit.

‘Angels Too Soon: The School Fire of ’58’ (Friday)

“Angels Too Soon” (different from the 2003 documentary of the same name) tells the story of the horrific school fire at Our Lady of the Angels that claimed the lives of 92 pupils and three nuns. This tragedy occurred so long ago that many younger Chicagoans may not have heard of it or have only a vague notion of the details — but it’s still relatively recent history, as we’re reminded through a series of interviews with survivors, including former students Matt Plovanich, Rosalie Guzzo, Ron Sarno and Concetta Bellino, who speak with moving eloquence about their individual experiences on the afternoon of Dec. 1, 1958, when a fire broke out in the basement of the school and spread with alarming rapidity through its corridors and hallways.

The episode begins with footage of the rock band Journey’s induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2017, as keyboardist Jonathan Cain, a former student at Our Lady of the Angels and survivor of the fire, says, “I would like to begin by thanking my father, who prophesied success from the time I was 8 years old after a terrible school fire, later said to me, ‘Son, don’t stop believing.’ ” (Many years later, Cain would co-write “Don’t Stop Believin’” with bandmates Steve Perry and Neal Schon.)

In present day, Cain echoes the sentiments of many of the survivors, who are still trying to comprehend why they were spared while others — in some cases their siblings — weren’t. “It just seemed unfair,” says Cain. “It seemed cruel. I was haunted by that.”

At the time of the fire, we’re told, Chicago had a population of 3 million, with some 2 million Roman Catholics and a total of 262 parishes. (To this day, many Chicagoans will identify where they grew up by naming their parish.) Our Lady of the Angels in Humboldt Park had a total of some 1,500 students packed into classrooms in a structure with wood interiors. There were no sprinkler systems, and there was a second-floor stairwell that lacked a fire door; safety codes of the time did not apply to schools that were built before 1949 — schools such as Our Lady of the Angels.

After a fire was started in a cardboard trash can filled with school papers in the basement, chaos reigned as smoke and flames engulfed much of the school. Some students stumbled through the black clouds and made it to windows, where they jumped or fell or were pushed out. Others were found at their desks, their hands clasped in prayers, or clinging to nuns who had tried in vain to save them.

Survivors talk about how there was no counseling back then, and how many in the community simply didn’t want to talk about the fire in the days and months that followed, even as funerals were held and many children were recovering at St. Ann’s Hospital. Even with a Cook County coroner’s inquest and reports a 13-year-old boy who had set fires at other schools had confessed to lighting a wastebasket at Our Lady of Angels, no one was ever charged, no official cause ever listed. As for the students who were spared that day, we learn that many went on to careers in fields such as law enforcement, teaching, nursing, firefighting. They were determined to make a difference with their lives.

‘The Race to Reverse the River’ (Sept. 29)

Officials stand near the construction site of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal in 1900.

Chicago Metropolitan Water Reclamation District

After watching this film, I’m STILL not entirely sure how humans working with late 19th century technology were able to reverse the direction of the Chicago River. This is not to say the filmmakers didn’t do an excellent job in laying out exactly how it happened; it’s just that it boggles the mind that Chicago was able to reverse the flow of the river away from the lake and toward the Mississippi River in one of the most impressive engineering feats in U.S. history.

We’re living in a Golden Age of the Chicago River these days, with tour boats and pleasure crafts and kayakers traversing the green-blue waters, anglers fishing from private boats or off piers, and thousands of locals and tourists enjoying the bustling Riverwalk and its medley of bars and restaurants and coffee shops. Flash back to the middle of 19th century, when the river was “treated like a sewer,” as our narrator so bluntly and accurately puts it, to the point where you could literally walk across the sludge and debris. You could be perfectly healthy one day, drink a glass of water, and within 24 hours you’d be dead of cholera.

After buildings were raised in central Chicago to lift them out of swampy grounds and intake cribs were implemented, more still needed to be done — and the only viable option was to dig a canal that would reverse the flow of the river. Enter the steam shovels and the dynamite!

Though somewhat dry in tone and filled with charts and graphics that make us feel like we’re sitting in an engineering class and it’s time to consider switching majors, “The Race to Reverse the River” is nevertheless fascinating and thorough. But don’t ask me exactly how they did it. They just … did.

‘Pullman and the Railroad Rebellion’ (Oct. 6)

Women board a Pullman train with help from a conductor (left) and a porter in a photo circa 1915.

Chicago History Museum

“Pullman” starts off as a profile of the engineer and visionary George Pullman, who made an indelible mark on the national landscape and on Chicago in the 1850s with his Pullman Palace Car Co., which re-created the luxury hotel experience on rail cars. For decades, freed slaves and their descendants worked as Pullman porters and Pullman maids, and after Pullman bought 4,000 acres of land and created the town of Pullman, many of these employees had the opportunity to live in homes with running water and gas lighting.

On the surface, it seemed like a good deal for those Pullman porters and maids — but the Pullman company was both employer and landlord, and after Pullman slashed wages and laid off workers, many didn’t make enough in wages to make rent. Porters worked killer hours, often getting only a few hours’ rest between shifts, had to survive on tips and put up with indignities such as the white passengers calling them not by their own names but “George,” after Pullman.

This episode segues into a story of labor and civil rights, with Asa Philip Randolph leading the charge to create the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, which led to porters getting higher wages, a cap on monthly hours and better job security. As for Randolph, he and Roy Wilkins worked for decades to organize what became the 1963 March on Washington. (Andre Braugher portrayed Randolph in Robert Townsend’s 2002 film “10,000 Black Men Named George,” and Glynn Turman will play him in the upcoming film “Rustin.”)

‘The Boss and the Bulldozer’ (Oct. 13)

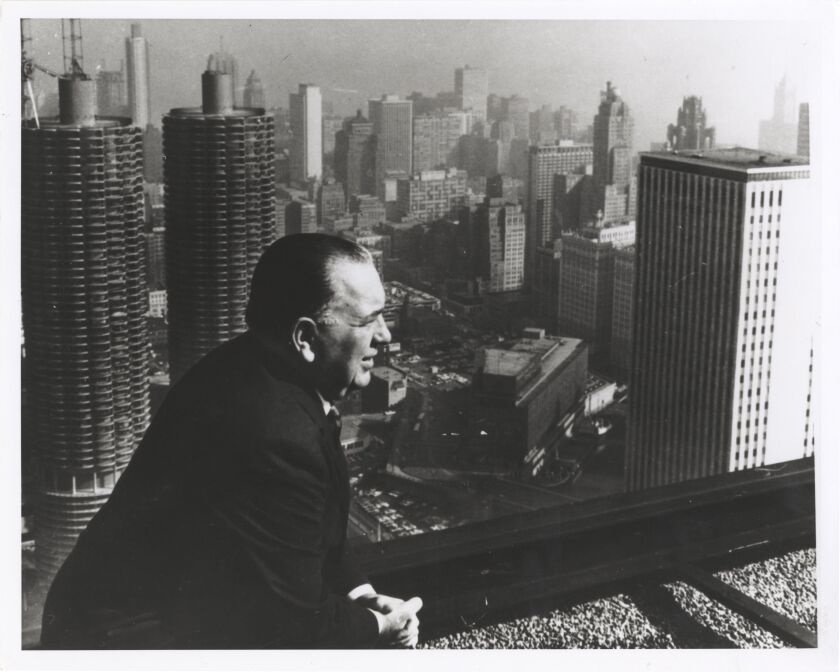

Mayor Richard J. Daley surveys the Chicago skyline, with Marina City in the background.

Richard J. Daley collection, University of Illinois Chicago Library

Another complex and generationally important Chicago story is told in Episode 4, which serves as a biopic of Mayor Richard J. Daley and a tribute to Daley’s visionary improvements to the skyline and the infrastructure — but also a condemnation of the mayor’s failed policies of urban renewal, which might have been well-intentioned but fostered poverty and segregation.

With esteemed veteran Chicago journalists and reliable storytellers such as Laura Washington, Lee Bey and Rick Kogan guiding the way, we’re reminded of Daley’s myriad improvements to the Loop business district and his championing of expressways, the rebuild of McCormick Place, the Chicago Civic Center (renamed the Richard J. Daley Center seven days after his death in 1976) and the “Circle Campus,” as UIC was originally known.

But some 800 homes and 200 businesses in and around Taylor Street were designated as “blight” and were bulldozed to make way for UIC. And with Daley in a battle with suburbia over the white middle-class, housing projects only served to segregate thousands upon thousands of Blacks from the mainstream of Chicago life, American life. Apartment buildings such as the Robert Taylor Homes were disastrous failures as they quickly fell into disrepair and were overcrowded, had broken elevators and faulty heating, and poorly enforced codes (if the codes were enforced at all).

There’s no denying that in the words of our narrator, “For better and worse, [Richard J. Daley] would dictate the shape of Chicago.”